Our Food

Creole Food

When the West Africans were brought to the Caribbean, they brought not only their ingredients but also their cooking methods. These methods were simple yet adaptable, blending with other influences over time and eventually becoming distinct features of modern-day Creole cooking.

These methods combined with relatively inexpensive and easy to find ingredients produced meals that were not only tasty but affordable for most. Hence, dishes like pelau, stews (oxtail, pork, beef, chicken), oil-down, “bake” and buljol, “fried bake” with fillings of choice, smoked herring, and couscous are staple diets for Trinbagonians. The quintessential Sunday lunch in T&T consists of callaloo, red beans, macaroni pie, provisions, and a stewed meat. A traditional regional soup called sancoche might also be served.

One of the main traits of Creole food is the communal-driven intent behind its preparation. Many of these dishes are “one-pot” or easily apportioned in order to cater for feeding a multitude of people. Eating was a community affair back when people employed their leisure time differently, and these foods facilitated a shared experience.

One of the most popular Creole food spots for breakfast and lunch today is The Breakfast Shed in Port of Spain.

Indian Food

During the era of East Indian indenture ship in Trinidad, colonial rulers realised that their workers would have to be fed food they were accustomed to from their homeland. Since most of the ingredients could not be sourced locally or even regionally, the British government imported substantial quantities of paddy rice, dhal (split peas), curry spices, and ghee from India.

The indentured workers were supposed to receive a rationed supply of foodstuffs from the commissaries on their plantations. However, unscrupulous officials would deny the Indians the full amount of their designated portions. Nevertheless, by the time the indenture ship period ended, items that were solely sourced for and used by East Indians could be found on grocery store shelves throughout the island.

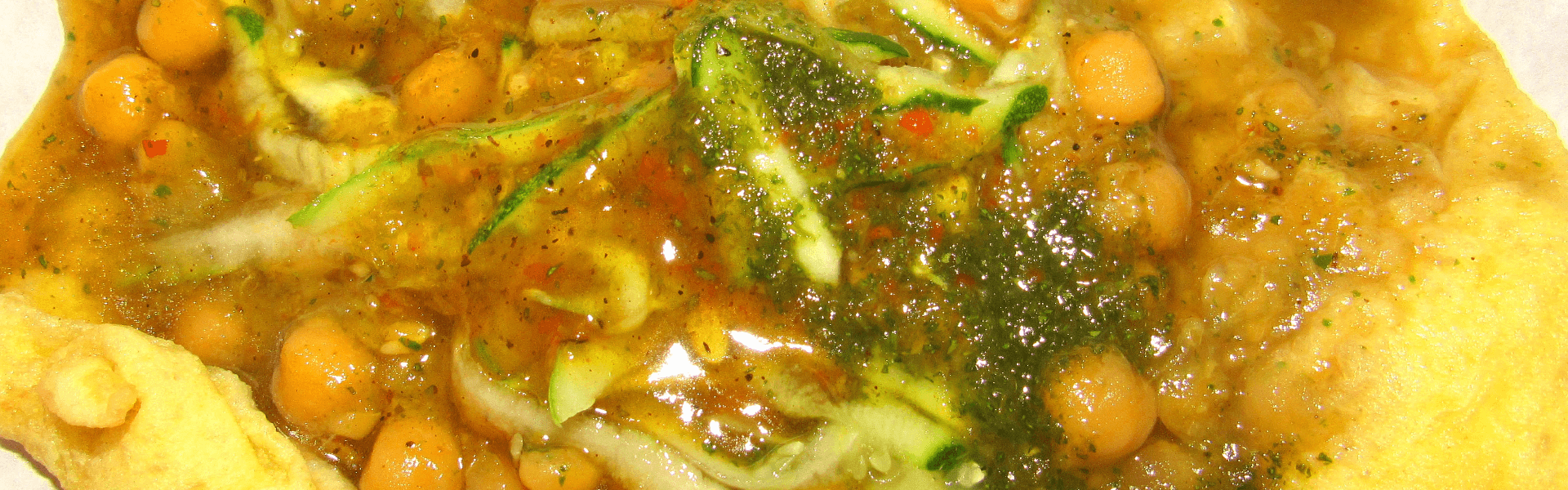

Food inspired by Indian cuisine is now a staple in most households and eating establishments in Trinidad. From the ubiquitous roti, to the ever renowned doubles and of course curried dishes like duck, chicken, and channa and aloo. Other popular *fast foods* of Indian origins are phoulorie, saheena, katchorie, aloo pies, pakoras, and samosas. Chokas are fried vegetables like baigan (eggplant), bitter melon, tomatoes, and potatoes, served with sada roti and eaten for breakfast. Chutneys are also prolific condiments or sides for various foods. Most commonly mango, pomme cythere, and even coconut are used as the main ingredient for the chutney. Another popular condiment is kuchela, a type of heavily seasoned pickled fruit (usually mangoes).

There are also many sweets, mainly served during Divali and Eid. Kurma, fat kurma, gulab jamoon, rasgulla, and barfi are the most well-known delicacies made for the festivities.

Chinese Food

The first set of Chinese immigrants arrived in Trinidad in 1806 aboard a vessel named Fortitude as part of Britain’s plan to augment their labour force the island. While it turned out that the Chinese were more suited to being tradesmen rather than being cane cutters, their contributions to our food culture is strong.

Almost every village in T&T has or had a Chinese “shop” or “parlour”. Typically a small space that seemed to be stocked with every item in the known world. Today large Chinese groceries are ubiquitous, but many arose from these small shops and parlours. In the past these corner stores were the only sources of “exotic” ingredients like soy sauce and bamboo shoots.

Apart from introducing new flavours, the abundance of Chinese restaurants in most areas of the country is a staple of our daily lives. There you can go to satiate cravings for chow mein noodles, pepper shrimp, or pow on your lunch hour. Most Trinidadians don’t even think about the history behind their go-to place for wantons, but they do appreciate its existence.

While the presence of these restaurants is nationally treasured and reflective of our diversity, Chinese food has not influenced Trinidadian cuisine in the same way that Indian or West African cuisine has. Dishes like roti and pelau are generally revered as local, they are often cited as paragons of our heritage and culture and spoken of with pride by citizens. But most people in T&T would not consider Chinese dishes culturally significant.

This might be due to the length of time that it took for the first wave of immigrants to assimilate into society. When they first arrived, most, if not all, of the ingredients they were accustomed to using could not be sourced. They were forced to simply make do with what was available. Over time when the ingredients became more accessible, they were used just as they had been used for centuries before, with very little influence from their neighbours’ pots. As a result, Chinese dishes were not adapted to suit the new climate and culture. Rather, they retained their original flavours and compositions, making them never truly local.

Nevertheless, T&T’s populace is greatly appreciative of our beloved Chinese food proprietors.

Street Food

Trinidad and Tobago is famous for its wide variety of affordable and filling street food.

In no particular order, they include:

- Doubles

- Saheena

- Aloo pies

- Pholourie

- Oysters

- Geera pork

- Corn soup

- Souse

- Coconuts

- Meat pies (beef, chicken, fish)

- Pies (cheese, potato)

- Currants rolls

- Gyros